New Year’s Day 1816. That was the occasion of the Blind Horse Ball in the Allen Tavern, Third and Main streets in Jamestown, that G. W. Hazeltine depicted in his Early History of the Town of Ellicott (pages 213 and 214). It was the first dance in southern Chautauqua County. However, another dance was being held that same day with equal gaiety in central Chautauqua County.

Judge L. Bugbee of the Centralia-South Stockton Bugbee family visited the home of Elias H. Jenner at the corner of Forest Avenue and Garfield Road, Busti, in 1859. There he met Abraham Pier, Jenner’s father-in-law. Pier, born in Great Barrington, Mass., in 1789, had come to Busti in 1812. Three years later he married Olive Marsh, Busti’s first school teacher. When Bugbee visited, Pier told him about the 1816 dance that had taken place two years before Bugbee’s birth. Nearly 100 years later Bugbee’s account of the story was collected by Clayburne Sampson. Copies of Sampson’s note books are now in the Chautauqua County Historical Society library with copies of some at the Fenton History Center.

“He [Abraham Pier] informed me that he and his wife came with oxen and sled, using blankets and a good quantity of straw in the place of fur robes, and calling on the way for Elisha Tower and wife (at Red Bird Corners); William Barrows and wife (same neighborhood) and (Abel) Brunson and wife (South Stockton), making when all were aboard, as gay a company as ever rode on an ox sled to attend a New Year’s ball.

“The cooking was mostly done across the road, at the residence of the old folks, where spare ribs, dressed turkeys and geese were roasting before the huge fireplace, suspended by two strings. The supper was thought to be hardly surpassed by anything the world had ever afforded.

“Then came the dancing, consisting of single jigs, French fours, the Monie Musk and a few reels. Music by John Acker, known far and near as ‘fiddling John.’ Love and war songs were very popular at such parties and a good singer was certain to be lionized. ‘The Stage Dream,’ ‘The Banks o’ the Dee,’ and ‘Wicked Polly’ would do to repeat if short of a greater variety. The party continued until the next morning, when all returned to their homes, having enjoyed the ‘sweets of friendship and unalloyed joy of kindred spirits’.”

According to the 19th century Stockton historian, Harlow Crissey, “John Acker had the distinction of being the first fiddler in the town. Dancing was a favorite amusement with many of the settlers. With only log cabins, and these generally having but one room, it required considerable tact to provide a suitable ball room; however, by turning the beds out of doors, or crowding them up chamber, sufficient space was provided for single jigs and French fours, and fiddling John secured considerable custom.” Crissey adds that Acker came to Chautauqua County in 1811 from Herkimer County.

Abraham and Olive Pier must have gone through Jamestown, ignoring the festivities there, and traveled all day on the ox sled without proper blankets and clothing to the South Stockton dance, picking up friends near their destination. They ate, danced, and sang all night, then took another whole day traveling home. No doubt the fun was worth the effort.

The dance was similar to other pioneer dances in this area and throughout the Northeast at that period. The one dance mentioned by name, the Monie Musk, a 1785 Scottish composition, is also the only one named in the account of the dance in Jamestown that same day.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, Richard and Carmen Gilman of Fredonia and their friends held parties featuring dances, singing and supper reminiscent of this antique account. The Irish single jigs have been replaced by the not so different North Carolina clogging. The French fours were similar to square dances.

The Monie Musk is an example of a contra dance in which the dancers assemble in lines rather than squares. Many of the contras done at the current parties were popular in 1816. Reels, another type of line dance, are included still.

The most interesting aspect of Bugbee’s account is his list of vocal favorites of Chautauqua County pioneers. This is the only list of song titles in our county from the pioneer period I have found in more than 50 years of research. Mark Cheney in 1920 wrote that exactly 100 years earlier, at the house warming of the later Henry Cheney home, “A portion of the evening was devoted to singing the old New England tunes from the American Vocalist.” However, he gives no song titles, and no general or music bibliography available today lists an American Vocalist until 1849. Also, not one of Bugbee’s four titles is among the large collection made by an Arcade family in the 1840’s and 1850’s and published in 1958 by Harold Thompson as A Pioneer Songster.

Historians have collected many of the dramatic and humorous tales of the arrival of our pioneer settlers. Genealogists have traced the further drama of their ancestors’ immigration to America and the relentless trek west of subsequent generations. But the drama and romance of the songs they treasured and carried in their heads and luggage, could it only be known, would be as rich as any of these other true-life adventures.

“The Stage Dream” was a popular song published in 1806 in the Jovial Songster by Stephen Jenks of Dedham, Massachusetts. The first line was. “How now, fellow! And what is all the news?” Such songsters were analogous in function to record albums in the late 20th century in spreading new songs and perpetuating old favorites.

“The Banks of the Dee” had already acquired the status of an old favorite by 1816. It was a Revolutionary War song from England about lovers parted by war. A stridently political American parody was probably the version popular here so soon after the War of 1812.

“Wicked Polly,” about a girl who preferred balls to church, was popular all over America in the 19th century. Edward S. Ninde in The Story of the American Hymn (1921) gives an account of its origin (which may be apochryphal).

Gershom Palmer, an itinerant preacher, used to hold services once a month in the village church of Little Rest (now Kingston) R. I. “When a young man, some years before the Revolution, he conducted the funeral of a girl by the name of Polly. She had scandalized the church people by her giddy behavior, and, when she died, after a brief illness, there appeared some verses entitled ‘Wicked Polly’.” Over the years both the anonymous folk and the publishers of songsters lengthened and modified the song as it spread geographically and increased in popularity.

The song that had the longest and most interesting journey to reach the primeval forest of Stockton as the sun dawned in 1816 was the one the singers called “Six Kings’ Daughters.” Scholars know it as “Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight” – number four of the 305 true folk-ballads of the English language assembled by Professor Francis James Child in the last half of the 19th century.

No one will ever know who composed this ballad or when but many theories about its origin have been advanced: it was written by a German minstrel and originally described the worship of the sun; it describes an incident that took place in Carrick, Ayrshire; it is a Scandinavian elf song or a German merman song; it describes the Comorre murders in 13th century France; it is about the death of the spirit of winter after six months represented by the six maidens; it expresses a subconscious desire for incest; or it derives from the Book of Judith in the Apocrypha.

We do know that by 1550 when the earliest surviving copies were written down, the ballad had spread throughout Western Europe in several languages. There are hints of the Middle Ages in many versions. Holger Olof Nygard conducted a thorough study (1958) and concluded it originated in Flanders.

The Flemish versions have the villain, Heer Halewijn, singing a magic song that entices the king’s daughter to put on resplendent clothing and ride into the woods to meet him. Although she grows tired and hungry, they ride until they come to a gallows field where seven women hang. Halewijn offers her a choice of the means of dying because she is the fairest of all his victims. She chooses the sword and then suggests he take off his silk clothing because a maiden’s blood spirts far and wide. While he is thus occupied, she seizes the sword and cuts off his head. The head speaks magically asking her to take his horn and summon his friends to comfort him as he dies. She pushes the head into a stream. On the way home she encounters the villain’s family. They ask where he is and she replies he had taught her his craft well and that he is now where he is served by seven maidens.

We cannot know what words were sung to the ballad in Chautauqua County, because no copy has been preserved here and ballads usually differ wherever they occur. However, American versions of this ballad show relatively little variation. A version sung in Washington County, Pa. in 1933 is typical. The villain, now nameless, persuades a maiden to take some of her father’s gold and two of his horses. The couple rides through the woods to the banks of the sea where the villain announces the maiden will be the seventh he has drowned there. He asks her to “take off that fine silk gown and hang it on a tree, for it is too fine and costly to rot in the salt water sea.” She asks him to “turn yourself three times around and gaze at the leaves on the tree, for God never made such a rascal as you a naked woman to see.” When he complies, she picks him up and plunges him into the sea to drown, taunts him and rides home.

This version closes with some confused conversations between the maid, her father, and a parrot, all grafted in from another ballad. Parrots appear in ballads as an attempt by later generations to rationalize talking birds, which were originally incarnate spirits. The maid’s name is Polin, derived by confusion between the parrot, Polly, and May Colvin, the name of the maid in Scottish versions.

Pennsylvania is 4,000 miles, 400 years, and two languages removed from the Flemish original and varies no more than you might find a gossipy rumor varying in a few months across town. Generations of people had sung the song, many believing it was a true story.

When the ballad moved from Flanders next door to northern France, the villain changed from supernatural to human, the sea shore locale was introduced and the change was made from villain disrobing to maid disrobing. All these changes were incorporated into English language versions.

The earliest known English copies date from 1776 or possibly 1710. All the English versions bear marks of decay and reworking by ballad mongers. By ballad mongers we mean printers in the 16th through 19th centuries who collected and reworked old songs and also invented new folk style songs. This was the country music industry of that day. The printers then sold their works on broadsides, paper printed on one side, words only, in the streets for a penny or less, the single records of the day. The broadside could indicate the new ballad used a familiar tune or the hawkers could sing the ballad as they walked the streets.

In the early 19th century J. H. Dixon bought a version of this ballad very similar to the Pennsylvania version for half a penny from a traveling minstrel near the Scottish border. In fact, the ballad mongers seem to have established a widely popular standard version of the ballad in both England and America early in the 19th century when our pioneers were singing it.

The pioneers were enjoying both old and new music that New Year’s Day. The dance style and the dance tune styles had originated in the17th and 18th centuries. A few older 17th century dances or tunes, such as “The Irish Washerwoman” may have been included that night. On the other hand, new dances and tunes in the same styles were being created every year. The vocal favorites included both recently composed works and older texts. The tunes for these songs also could be new compositions or recyclings of ancient ones. An example of the latter is the tune used for “Captain Kidd” and numerous other songs since the 18th century. The tune itself can be traced to the 10th century.

Throughout American history dances have evolved. Linear contra dances lost popularity to squares; someone invented calling, the waltz and other European dances were introduced; singing calls appeared, all in the 19th century. In the 20th century Western or club square dancing divided and modified the square dance phenomenon while electric instruments changed the sound of the bands. Late in the 19th century, the cities parted from the rural areas in dance tastes with wave after wave of new dances that eventually relegated square dancing to rural areas.

Although the ancient ballads survived in some isolated parts of the United States, “Six Kings’ Daughters” was probably never sung by the next generation after Chautauqua’s pioneer settlers. New musical styles flooded the nation. Sheet music parlor ballads, minstrel shows, then the new hymnody of Lowell Mason, marches, opera, barbershop, jazz, and big bands came on the scene followed by rock and roll.

ADDENDUM

We know that Amos Sottle, a native of Vermont who had grown up in Chenango County, built a cabin and was tending cattle owned by a Buffalo man at Cattaraugus Creek, now Irving, by October, 1796. Information derived from Everett Burmaster that has come down through a typed page marked 1933 with Clayburne Sampson’s initials on it claims that Sottle played the fiddle for the Indians at an early date. The dreams or revelations of Handsome Lake upon which a new religion was built, began in June, 1799. They specifically condemned fiddles and fiddle music. Christian or secular Indians, however, it was pointed out, could enjoy the same music and dancing as anyone else. (Although we should note that certainly the Baptists, and several other denominations would excommunicate members who consistently or blatantly attended balls, especially if they drank.) So, it is possible that as many as16 years before any other surviving evidence, traditional music was played in Chautauqua County thanks to Amos Sottle.

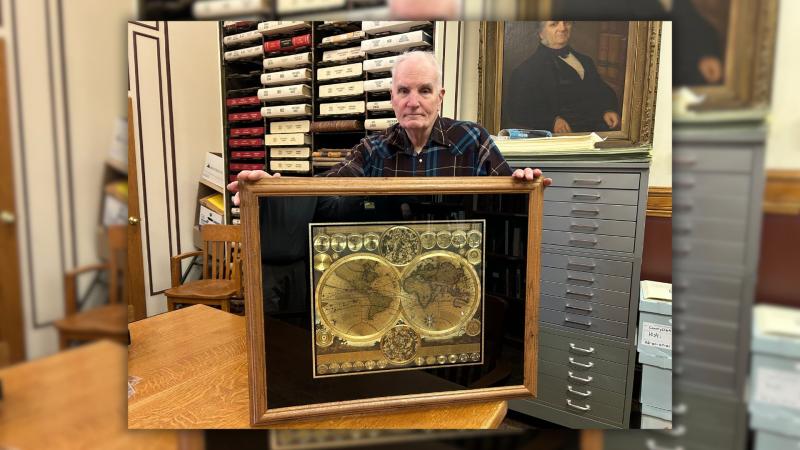

Sottle is known to have constructed a fiddle around the skull of a horse. This fabulous instrument survives at the Hanover History Room in Silver Creek. We don’t know when Sottle constructed it. We can’t say it was the only or the first fiddle he owned. And we don’t have any names for the tunes it has played.

We should also take note of another two dances in 1816, both on the Fourth of July, one in Busti (then called Frank Settlement) and one in Jamestown (both Busti and Jamestown then in the Town of Ellicott). The Busti dance, apparently the larger and more successful, is described on page 331 of Andrew Young’s History of Chautauqua County. Ebenezer Davis, older brother of Busti’s Emry Davis, the strict Baptist, was the fiddler for the evening dance.

The two July 4 parties were primarily Independence Day celebrations and were politically charged and segregated. The nationally victorious Republicans, later called Democrats but not to be confused with members of the modern party of the same name, in Busti and the Federalists in Jamestown. Six Revolutionary War veterans were in attendance at Busti.

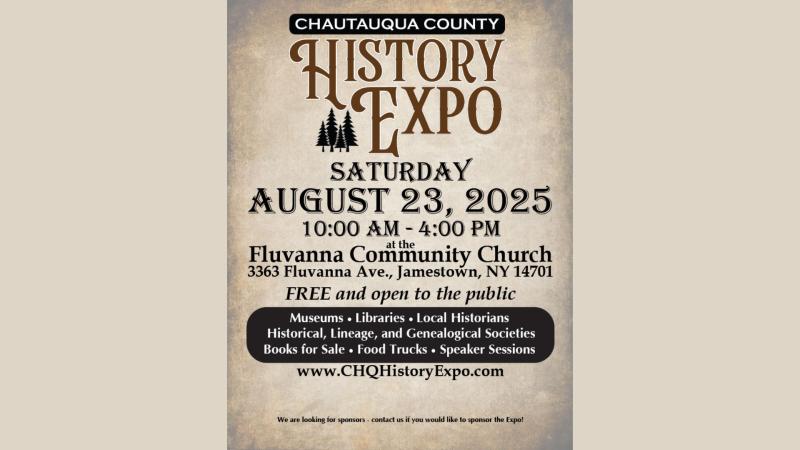

Norman Carlson, 1984. Revised 2025